Safeguarding Mediterranean Giants

© naturepl.com / Luis Quinta / WWF

In the sparkling blue waters between France, Italy, and the island of Sardinia, Mediterranean fin whales will soon begin to congregate.

Every summer, the enormous yet graceful whales – the second-largest animal on Earth, growing up to 22 meters long – come to the Ligurian Sea to feed on large swarms of krill.

This highly productive area is a hotspot for cetaceans – providing critical feeding and breeding grounds for fin whales, sperm whales, dolphins, and many more species. To protect the remarkable marine mammals found here, the Pelagos Sanctuary – spanning an area of 87,500 square kilometers – was established by France, Italy, and Monaco in 2002 as the first transboundary marine protected area (MPA) to protect cetaceans.

But it’s far from a haven for these ocean giants. Here, one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world puts fin whales in the direct path of massive tankers, cargo ships, and high-speed ferries that criss-cross their waters.

Navigating a sea of ships

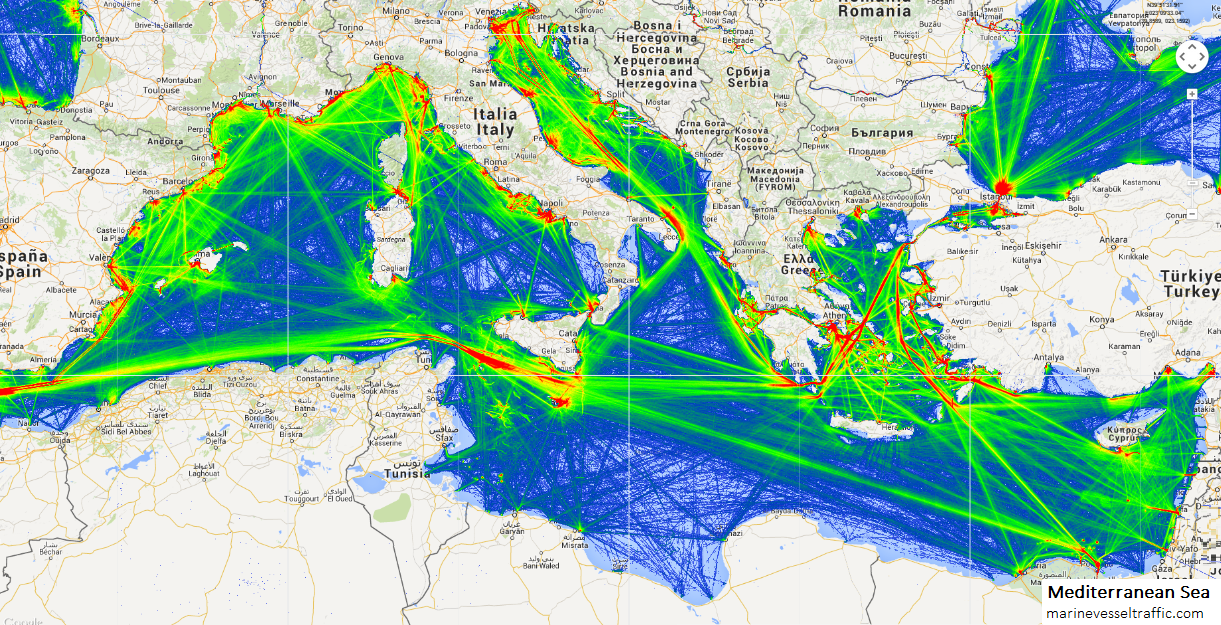

Although it covers less than one per cent of the world’s ocean, up to 30 per cent of the world’s global shipping traffic is concentrated in the Mediterranean Sea. In the last twenty years, the volume of maritime traffic has almost doubled here – with vessels increasing in both size and speed – and it is expected to double again in the next 15 to 20 years. In the Pelagos Sanctuary, the threat is amplified as tourists flock to the region in the summer months when fin whales come to feed.

Ship traffic density map of the Mediterranean Sea from www.marinevesseltraffic.com

As a result, the risk of ship strikes is 3.25 times higher in the Pelagos Sanctuary than the rest of the Mediterranean – killing up to 40 fin whales each year. Many more are severely injured by collisions with ships and impacted by high levels of vessel noise. For this small and isolated Mediterranean subpopulation of about 1,720 mature individuals, the death of even a few animals threatens their survival.

Globally, the volume of shipping traffic worldwide has increased 300 per cent over the past two decades, with some of the busiest ports and channels overlapping important whale habitats. Ship strikes are now one of the leading causes of human-induced mortality for several whale populations, including fin whales, which are considered globally vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) after decades of commercial whaling. In the Mediterranean, the fin whale subpopulation is considered endangered on the IUCN Red List and was identified as at-risk by the International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) Strategic Plan to Mitigate the Impacts of Ship Strikes on Cetacean Populations.

"Fluker” the fin whale became well known in 2013 when she was spotted in the Pelagos Sanctuary with half her tail (fluke) missing, most likely lost in a collision with a sea vessel. Fin whales rely on their tails to dive hundreds of meters to feed on krill. In 2020, WWF-France found Fluker with the other half of her tail sheared off, extremely thin and unable to feed herself. © WWF France

In addition to ship strikes, resident fin and sperm whales are at risk from a range of human activities in the Mediterranean. Cumulative impacts include underwater noise pollution from vessels and oil and gas development – which affects the animals’ ability to locate food, find mates, navigate, and communicate; climate change – which affects their prey distribution; and plastic pollution – which affects many biological processes such as growth and reproduction. In the Mediterranean, the density of microplastics is among the highest in the world; resident fin whales are thought to be swallowing close to 2,000 microplastic particles per day.

Monitoring a sea under pressure

Théa Jacob, WWF-France

Based in Marseille, Théa Jacob, Marine Species and Sustainable Fisheries Officer for WWF-France, has witnessed growing pressures in the region first hand. She collaborates with stakeholders across the Mediterranean as well as international organisations – equipping industry, policy makers, and governments with evidence and tools to respond to challenges to protect fin whales and other marine species.

To better understand the Mediterranean’s cetaceans, Théa takes part in WWF’s Cap Cétacés programme – conducting vital research on populations and distributions, genetic structure, and threats from chemical pollutants and microplastics. She remembers one of her first experiences aboard the Blue Panda: “I was feeling a bit seasick so I was sleeping on the outside of the boat. One night I was woken up by an incredibly loud sound of spouting air from a blowhole. It was a magical encounter – just the whale and I in the middle of the night, she was passing so closely and slowly to the anchored boat.”

For the last two years, the team has pivoted their focus to study cetacean movement patterns and behavioural response to shipping traffic. This June, Théa will join them again – attaching suction cup tags and a camera on the back of the whales to record the position, depth, and movement of the animal. This will be overlapped with ship tracks (based on ships’ Automatic Identification System) to map distribution of whale hot spots along shipping lanes and establish priority areas for conservation measures in the northwest Mediterranean.

Théa explains: “We’re seeing how whales react when they come across a ship or ferry: do they dive deeper, do they turn around, do they change their route? These behaviour changes, especially if repeated over time, are likely to have a negative impact on the individual’s energy expenditure and long-term health, which could eventually result in lower reproductive rates and population declines. This may be especially true for small populations like Mediterranean fin whales. This data is critical to informing appropriate mitigation measures to reduce collision risks.”

For more than 20 years, field research conducted from WWF’s Blue Panda – through the Cap Cétacés programme – has improved our understanding of whale distribution and important foraging areas. © WWF France

Advocating for effective protection

Despite their benefits, if not effectively managed, MPAs are limited in their ability to conserve marine ecosystems. The designation of a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA) – a global mechanism developed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the UN authority for global regulation of shipping – is another conservation approach. Unlike MPAs, which aim to protect marine ecosystems from a variety of human activities, a PSSA deals exclusively with protecting sensitive marine environments from the adverse effects of shipping. Théa has been heavily involved in the process, which requires considerable collaboration between researchers, regional stakeholders, national governments, and the IMO:

“WWF has been advocating with government representatives of France, Italy, Monaco and Spain to propose a PSSA in the North Western Mediterranean. This would include strong and effective mitigation measures to reduce ship strikes in the region, such as speed reduction and alternative routes to divert traffic from whale populations. It would also raise global recognition of the significance of the region and make a strong statement on the importance of protecting it. We look forward to the submission of the final proposal by governments to the IMO by the end of this year.”

Because whales move between different ecologically interconnected areas – where they feed, mate, give birth, nurse young, socialise or migrate – connecting MPAs is just as critical. With only 2.48 per cent of the Mediterranean Sea currently covered by MPAs with a management plan, only 1.27 per cent by MPAs that effectively implement their management plan, and only 0.03 per cent by fully protected areas, the current level of marine protection in the region is ineffective for cetaceans. WWF is advocating for at least 30% of the Mediterranean Sea to be effectively protected by 2030 by creating a network of connected MPA and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) distributed across political boundaries and ecoregions.

With Mediterranean fin whales – and cetaceans around the world – facing an uncertain future from shipping and other growing threats, we must do all we can to minimise the impacts and protect the waters they rely on to survive.