On a quiet mission

© Paul Nicklen / National Geographic Creative / WWF-Canada

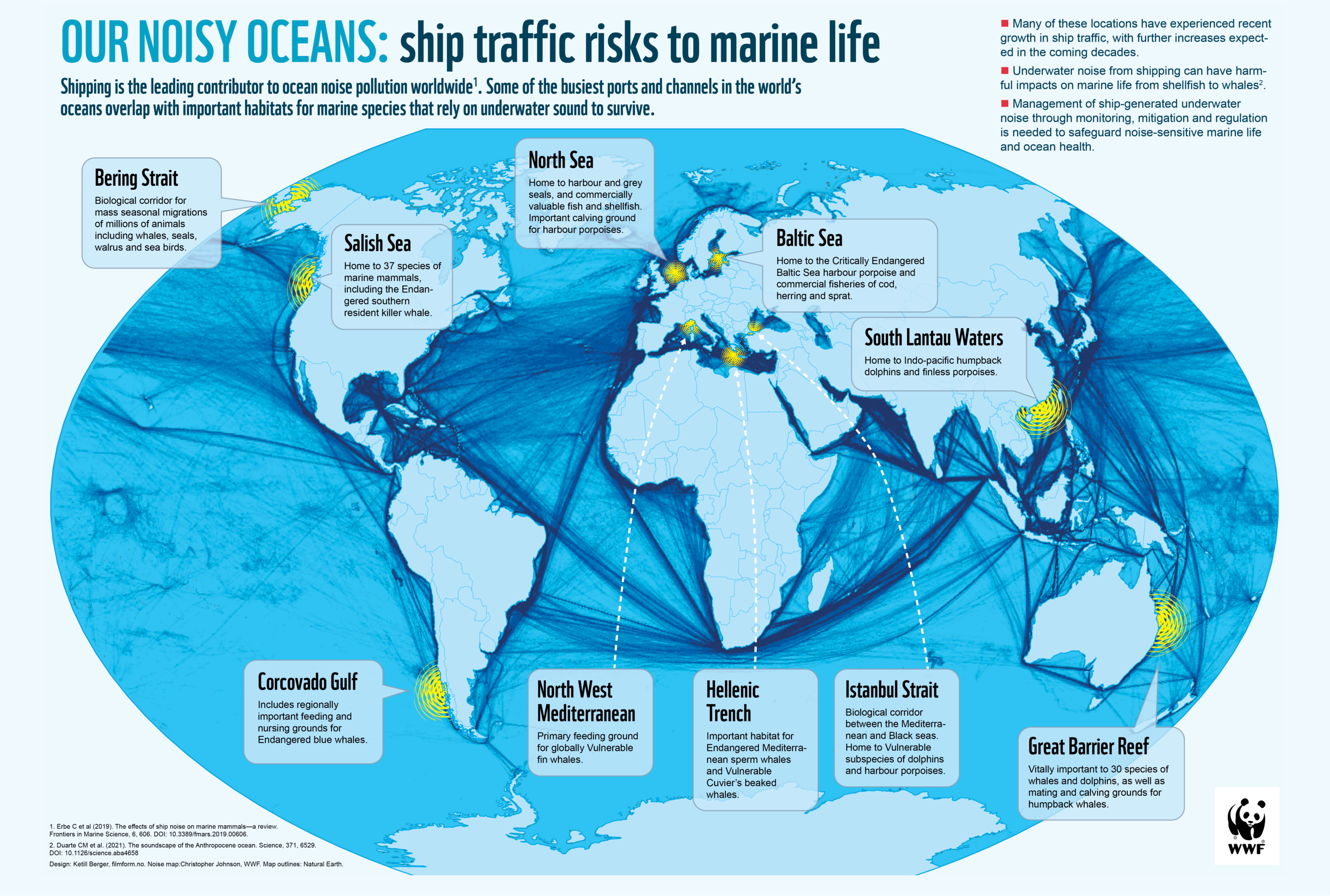

With whales and dolphins under acoustic assault from ever increasing shipping traffic, we need to turn down the volume and talk up the solutions for the health of our oceans, as WWF’s Senior Specialist for Arctic Species, Dr Melanie Lancaster, explains.

What does a healthy ocean sound like? The answer can be found in the Arctic, where humans have yet to substantially pollute the soundscape. Here, vast tracts of sea ice blanket the ocean, muffling the roar of wind and waves. In the watery depths below, marine animals – among them narwhals, belugas and bowhead whales – navigate the darkness, communicating with each other, finding a mate, averting danger, primarily through their sense of sound.

Dr Melanie Lancaster has had the chance to listen in with the help of underwater microphones while doing field work in the Canadian high Arctic. “WWF is supporting research to understand the baseline soundscapes narwhal are experiencing in this region. There has been a recent increase in shipping associated with an iron ore mine, which could have impacts on narwhal, seals and other marine animals.”

Solutions to pollution

WWF is acting on multiple fronts, including through the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization (IMO), a global regulator of shipping, where it’s working to get underwater noise back on the agenda. (The issue was last tackled a decade ago, resulting in voluntary guidelines that have not been taken up by the shipping industry.) When we catch up, Dr Lancaster has just finished presenting a webinar on the issue to 250 policy and technical experts, including IMO delegates, and she’s in a buoyant mood.

“It was a really good session – there was a lot of interest and positivity about supporting this work. From a group focusing on underwater noise impacts to another looking at designing ship propellors to create less underwater noise – there’s a lot of work happening. It was heartening to hear and be part of it.”

As an observer to the Arctic Council, WWF has also been working on the issue with the council’s eight member states. “When we started talking about underwater noise with the Arctic Council about four years ago it really wasn’t on their radar – noise was underestimated as a pollutant,” says Dr Lancaster, who is now seeing a shift in states’ willingness to address the problem.

Meanwhile, WWF national offices are working with governments on better management of ship-generated underwater noise in their territorial waters, and with shipping companies to reduce their environmental impact. As work with industry evolves, WWF plans to share this information with the public so they can make informed choices about how they choose to have their goods shipped, who they go on a cruise with and which ferry operator they use, so that pressure comes from the consumer side as well.

“Our national offices are also supporting research and acoustic monitoring to understand the impacts on whales and dolphins and other species, so we can make good recommendations for how the problem should be addressed,” says Dr Lancaster. “We’re a global network so we’re really well set up to work at all these different levels. It’s a complex issue and we need multiple irons in the fire at all times to keep things moving.”

Making noise to turn down the noise

WWF’s supporters are a critical part of the solution for protecting our oceans. Already, over 80,000 people have signed a petition for governments to keep underwater noise at safe levels for Arctic biodiversity, which WWF has presented to the Arctic Council and the IMO.

“When we go to these international fora, these sorts of things have an impact,” says Dr Lancaster. “When you’ve got high-level government representatives sitting in a room it makes a difference for them to know that the public cares about this issue and wants something done about it. We need to continue to make noise to turn down the noise, and we need our supporters to help us do that.”

Dr Melanie Lancaster of the WWF Arctic team.

Related links

Download the WWF report launched on World Ocean Day 2021 : Shipping and Underwater Noise, A growing risk to marine life worldwide.

WWF Arctic Programme: Noise pollution from Arctic shipping more than doubled in six years putting whales and other marine life at risk (May 2021)

Learn more about Dr Melanie Lancaster’s conservation work at WWF.