Fishing for the future

© WWF Pakistan

“What would happen when my son asks me, will I ever see these dolphins in the sea, or will I only see them in books?” For WWF’s Umair Shahid, protecting whales and dolphins is more than a conservation imperative – it’s deeply personal. Here he explains how WWF is taking on fisheries bycatch, one of the greatest threats to whales and dolphins worldwide.

Umair Shahid’s life-long love of whales and dolphins began on a fishing trip to Churna Island in the Arabian Sea. He was ten years old.

“That’s when I first saw a live dolphin,” he recalls. “My uncle was fishing with squids as bait and a bottle-nosed dolphin had accidently become caught in the line. He dived into the water and took the hook out of its mouth, then the dolphin came back asking for food – for us to ‘apologize’. She took the bait and was very happy. I was amazed, and that kind of intelligent behaviour stuck in my head.”

Twenty-six-years later, Umair is now leading WWF’s tuna fisheries work in the Indian Ocean to protect marine animals, including whales and dolphins, from a range of threats. The greatest of these by far is entanglement in fishing gear, known as bycatch, which kills an estimated 300,000 whales, dolphins and porpoises (cetaceans) globally each year.

Numerous studies show a direct link between declining cetacean population numbers and interactions with fishing gear, yet not enough is being done to stop this unwanted and unnecessary cause of death. Proven solutions exist, from working with fishing communities to test and use safer fishing gear, to improving fisheries management and strengthening legislation on bycatch. Umair has worked on all three fronts, supporting conservation efforts in Pakistan and the Indian Ocean region more broadly, including through the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) and its member states: Maldives, Sri Lanka, India and Iran.

Working with fishers

Working from the ground up has been a key part of WWF’s strategy, and Umair cites his work with fishers, skippers and boat owners on a major research project in the Pakistan tuna fleet as a successful example of this approach.

“When I started working in WWF’s Pakistan office, we knew there was a big problem with cetaceans and bycatch, and we knew we had to make changes from the ground. We took a citizen-science approach, developing an incentive-based mechanism where fishers would provide us with data and images of everything they were catching, and in return we could implement our ambitious ideas for fishing sustainably, applying a toolbox of approaches such as using LED lights as visual deterrents.”

“I’ve been on one of these vessels as an observer and it’s challenging, but we train the skippers and the fishers how to handle the cetaceans once they’re entangled; they check for injury and release them back into the sea. That’s what brings me a lot of hope, if we can educate fishers to make a change it will work – and it is starting to work in Pakistan.”

© WWF Pakistan

Integrating conservation science into fisheries management

A lack of scientific data detailing the full extent of cetacean bycatch in the region remains a significant challenge. Recent studies estimate 60,000 cetaceans are dying each year from bycatch in the Indian Ocean, and a major study published last year estimates four million small cetaceans have been caught as bycatch in commercial tuna fishing nets since 1950. It’s an alarming set of numbers, highlighting the urgent need for much improved monitoring, mitigation and management.

Currently, Umair is the Indian Ocean Tuna Manager for WWF and works closely with the IOTC and its member states to improve fisheries in the Indian Ocean, but also management of associated species that fall within the IOTC’s remit.

“WWF is tackling bycatch at a high level – both at the IOTC and the International Whaling Commission through its bycatch mitigation initiative. We know we need to work with governments and the next generation of people who are coming through, especially high-level politicians and ministers engaged with fisheries,” says Umair.

“We need to ensure that appropriate tools and governance mechanisms are strengthened, recognizing and prioritizing improved management – breaking the status quo of working with a single species approach.”

Umair Shahid of WWF © WWF-Pakistan

Extinction risk “real and imminent”

Umair stresses that this work is urgent, with action needed now to tackle bycatch – arguably the greatest marine conservation issue of our time – and the numerous other threats impacting marine species, many of which face extinction within our lifetimes. For whales and dolphins, this extinction risk is “real and imminent” according to more than 350 scientists and conservationists – WWF experts among them – who signed an open letter in 2020 calling for global action to protect cetaceans from extinction. More than half of all species are of conservation concern, including several that inhabit the Indian Ocean.

“In 2021, we know that fish stocks are in decline and that three of the major fish stocks of tuna are being over-fished in the Indian Ocean” says Umair. “We also know several marine species are on the verge of extinction. Fewer than 100 Arabian humpback whales remain in the Northern Indian Ocean, for example, and Indian Ocean humpback dolphins are listed as endangered on the IUCN’s Red List.”

In the Indian Ocean, the threat of bycatch to marine cetaceans and lack of data poses serious risks, WWF has been advocating at the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission’s Working Party on Ecosystem and Bycatch for undertaking a series of workshops on multi-taxa bycatch mitigation with the first one being focused on drift gillnets, followed by longline and purse seine among others. While bycatch mitigation is one of the biggest challenges of today, we need to prioritize cetaceans conservation and bring it to the forefront of the agenda for all governments.

Solutions are emerging but need more dedicated research now

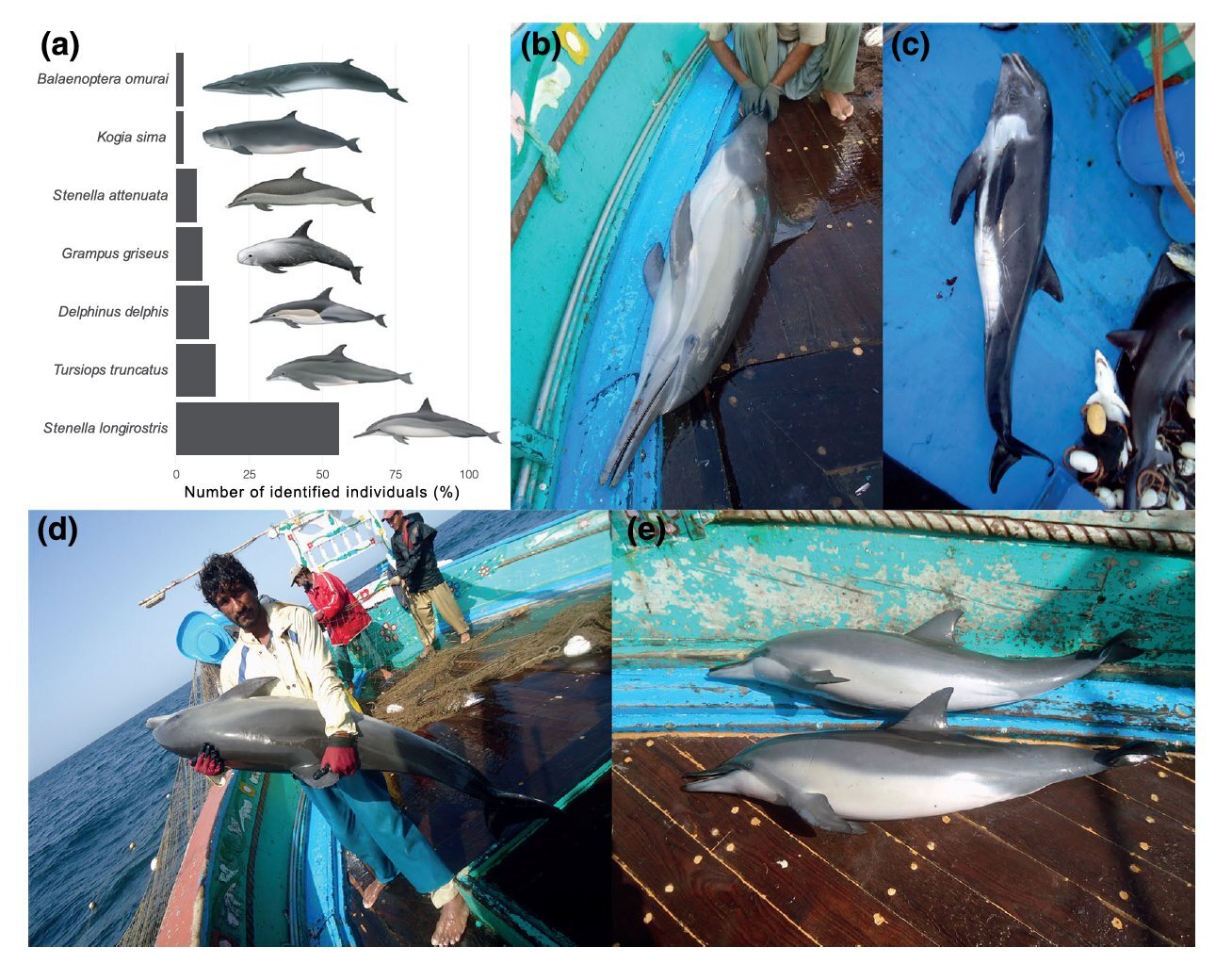

Umair is the co-author of a new study published this week led by Jeremy Kiska of Florida International University with a team from WWF Pakistan examining techniques to reduce the chances of tuna fishermen accidentally pulling dolphins and whales by lowering gillnets into the water instead of using them on the surface..

In a study of fishing methods used in Pakistan’s semi-industrial tuna gillnet fishing the team found when a gillnet was placed about 6 feet below the surface, bycatch of dolphins decreased by 78.5%. Given the high rates of whales and dolphins being accidentally captured each year by gill nets in the Indian Ocean, the potential for lifesaving is immeasurable.

“What would happen when my son asks me, will I see these dolphins in the sea, or will I only see them in books? This scares me – that my son may not have the same experiences as me. We need to make sure that the leaders of today will be responsible and accountable to the next generation, and not be afraid to voice our concerns.”

Photos from Kiska et al 2021 - https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3706

For more information visit:

Kiszka, J.J., Moazzam, M., Boussarie, G., Shahid, U., Khan, B. & Nawaz, R. (2021). Setting the net lower: A potential low-cost mitigation method to reduce cetacean bycatch in drift gillnet fisheries. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 1– 9. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3706