Whales without boundaries - why the high seas matter

June 30, 2022

© Shutterstock / Craig Lambert / WWF

Vast expanses of our global ocean are unprotected – putting whales and other marine life at risk. A historic Global Ocean Treaty now in negotiations offers hope to better manage and protect biodiversity on the high seas.

Beyond the jurisdiction of any country, the vast areas of the high seas cover nearly two-thirds of the global ocean and account for 95% of the habitat occupied by life on Earth. From microscopic phytoplankton on the surface, to coral reefs in the deep sea, to millions of undiscovered species, and enormous whales that cross entire ocean basins—these expanses teem with life. This rich biodiversity generates half the oxygen we breathe, helps mitigate the climate crisis, and harbors innumerable new scientific discoveries.

Yet the high seas are one of the least managed places on Earth.

Navigating the high seas

Whales provide valuable insight into how important international waters are for migratory marine species. A recent report by WWF and science partners, Protecting Blue Corridors, visualises 1,000 of these migrations across the world—one humpback whale covered 18,942 kilometres across the Southern Ocean over 265 days, spending half its time in the coastal waters of 28 countries, and the other half in the high seas. Another study showed 14 different marine species—from leatherback turtles to white sharks—spent three-quarters of their annual cycles in the high seas. Whale migration often occurs across the boundaries of many nations, weaving in and out to international waters.

Protecting Blue Corridors provides a comprehensive look at whale migrations and the threats they face across all oceans. The high seas are the areas outside the 200 nautical mile limit of any nation's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

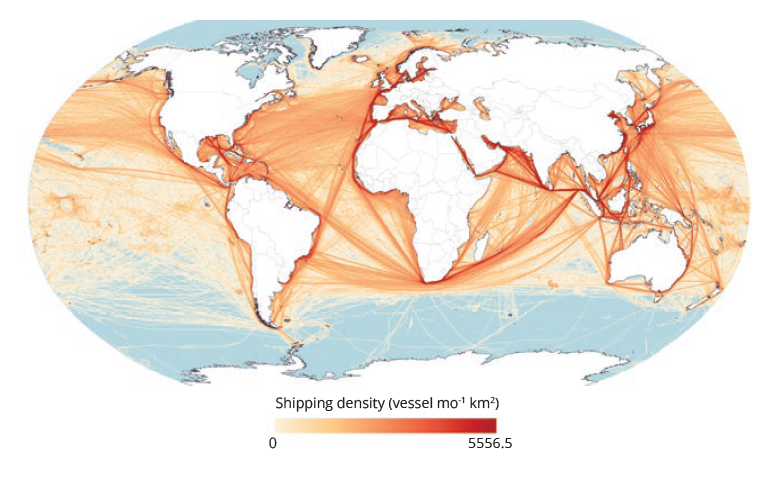

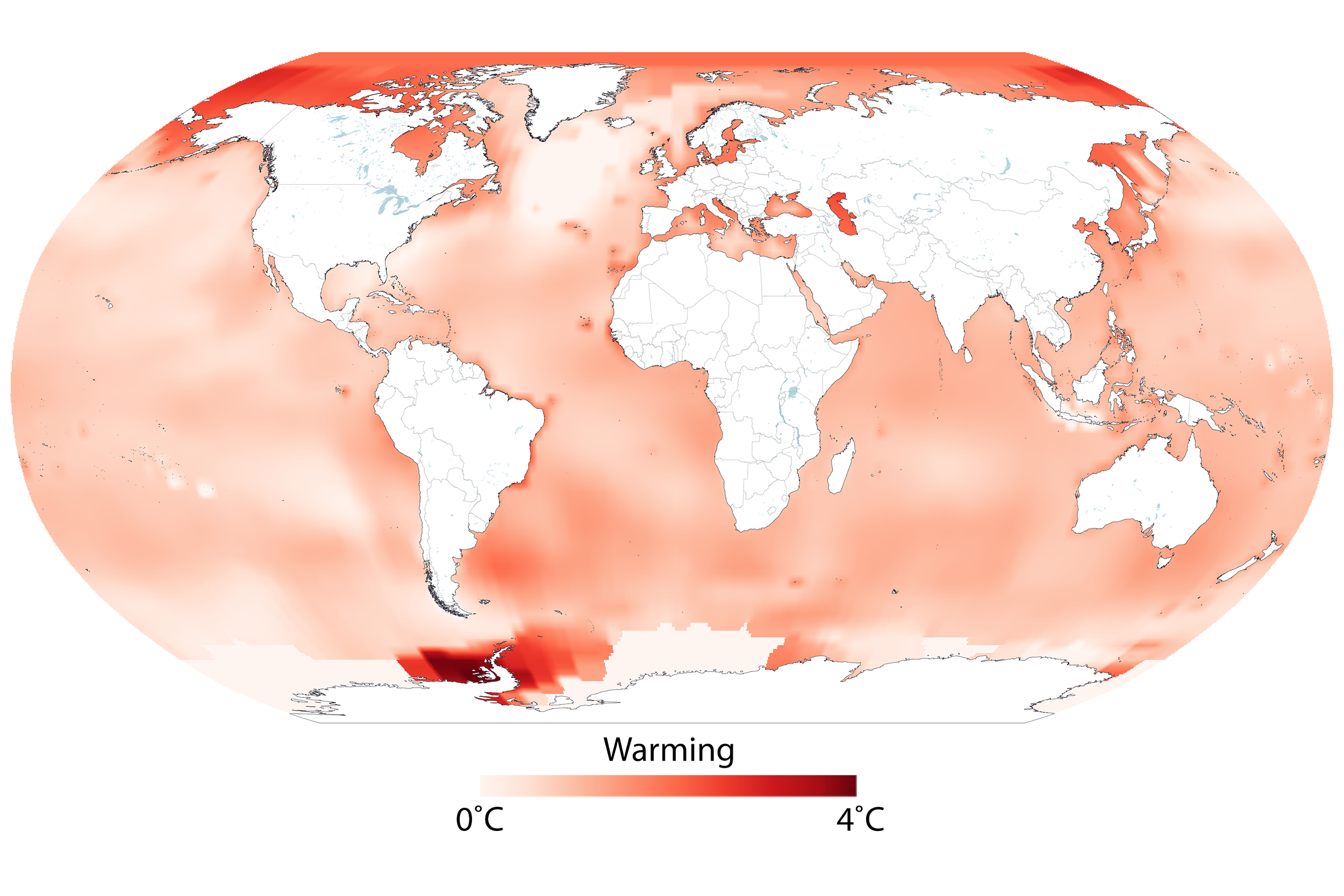

But with just 1% of the high seas protected, these species are under pressure from global shipping traffic, fishing operations, plastic pollution, and impacts from climate change that now reach nearly every area of the global ocean; while emerging activities such as deep seabed mining pose new threats. For whales, these overlapping stressors in their key habitats are impacting recovery of some populations, and driving severe declines in others.

Multiple human threats are impacting whales – including shipping, industrial fishing, and climate change (L-R) – within both critical habitats and along their migration corridors (Johnson et al 2022).

Chris Johnson, Global Lead for WWF’s Protecting Whales & Dolphins Initiative, said “An estimated 300,000 cetaceans are killed each year as a result of entanglement in fishing gear. Six out of the 13 great whale species are now classified as Endangered or Vulnerable, even after decades of protection. With just 336 animals left, North Atlantic right whales are at their lowest point in about 20 years. We need a way to enhance cooperation to implement urgent solutions agreed between national governments and international policy agreements to tackle the growing cumulative impacts for whales, so they can recover and thrive.”

New hope for protecting our global commons

The good news is, momentum to protect the high seas is building. Final negotiations will soon be underway to create a landmark global framework, the UN treaty to manage marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ), also known as the Global Ocean Treaty—a legally binding instrument to enable the protection of marine life and habitats in these international waters.

After more than a decade of discussions, progress has been slow to get a Global Ocean Treaty over the line. Earlier this year, the fourth negotiating session did not reach agreement, prompting the need for further deliberations this August. Jessica Battle, WWF’s Senior Global Ocean Governance and Policy Expert, said: “More than 50 countries have now committed to finalising the Global Ocean Treaty in 2022. Now, we need to close the gap between promises and actual protection of the high seas. WWF is keen to help governments deliver a robust mechanism to sustainably protect and manage these resources that belong to all of humankind.”

Fragmented framework is failing our ocean

For decades, governments have been able to create marine protected areas (MPAs) in their national waters to help preserve habitats and species, while strengthening the ocean’s resilience to multiple stressors – including climate change. But in the high seas – beyond the 200 nautical mile (370 km) reach of any country’s jurisdiction – the legal and enforcement mechanisms to establish and effectively implement MPAs are lacking. Meanwhile, the patchwork of international bodies and treaties that aim to manage human activity in the high seas – such as shipping and fishing – vary greatly in their scope and objective, with no mechanisms to coordinate across geographic areas and sectors.

As a result of these legal and logistical challenges, international bodies have created only a handful of high seas MPAs, while the vast majority are in national waters. While 18 per cent of national waters are designated in MPAs; in contrast, just 1 per cent of the high seas are protected – most of which is within the nearly 2.06 million km2 Ross Sea MPA. Altogether, 8 per cent of the global ocean is protected, while strongly or fully protected areas cover less than 3 per cent – falling far short of the recommendation by scientists to protect at least 30 percent by 2030 – known as the “30x30” pledge.

A robust Global Ocean Treaty – being developed under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) – is an unmissable opportunity to fill these governance gaps and reach the global 30x30 target. Critically, the treaty would provide legal mechanisms that allow States to establish MPAs in the high seas – allowing connected networks of protected areas to be created across national and international waters, creating meaningful links between key habitats for whales. To ensure effective protection, these areas should be located where the conservation need is most urgent, have enforceable management measures, be large and potentially mobile to enable species to shift and adapt as conditions change, and complemented by other mitigation measures—such as ships slowing down, or quick release fishing gear.

Cross-border collaboration to connect protected areas

Despite obstacles to establish networks of MPAs on the high seas, the emergence of such regional cooperative mechanisms hold promise. Most recently, the launch of a coalition by nine countries aims to establish a network of connected MPAs along the Pacific coast of the Americas, from Alaska to Patagonia. The project expands upon the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor (CMAR) – an initiative declared by Panama, Ecuador, Colombia, and Costa Rica in 2004 to establish a fishing-free network of interconnected MPAs – protecting more than 500,000 km2 of ocean habitats in one of the world’s most important migratory routes for whales, sea turtles, sharks and rays. In the Southern Ocean, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) agreed to implement the largest MPA on earth in the Ross Sea to protect over 2 million km2 and have commited to implement a network of MPAs around the continent.

For a healthy ocean and planet, we need whales to recover and thrive. Right now, we are at an important crossroads for making that happen. The UN Ocean Conference and fifth session of the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction are key opportunities for governments to take bold action to establish and connect networks of protected areas across national and international waters covering at least 30 per cent of our ocean by 2030.

“Studying whales’ critical habitats, including their migrations, shows us how connected our ocean is. But varying levels of protection along their migration superhighways – or none at all – is a risk for our ocean giants. An ambitious Global Ocean Treaty is our chance to connect important critical habitats to preserve ecological connectivity across their ranges and help conserve the broader high seas ecosystem. With growing evidence showing the vital role whales play maintaining ocean health and our global climate—protecting these blue corridors is critical for our own future, too,” said Johnson.