Whales’ frozen lifeline - polar feeding grounds

13 February 2025

A humpback whale breaching the surface in the Antarctic. © Logan Pallin / UCSC. Photo taken under a scientific permit.

A story on how declining sea ice could be catastrophic for whales around the world, unless we act now and protect these creatures for future generations

Lunging, the whale gobbles up a huge mouthful of ice-cold water, devouring the miniscule prey caught inside. An individual humpback, like this one, can engulf nearly its bodyweight in water in one mouthful, but each gulp only contains a small amount of krill (tiny shrimp-like crustaceans). Over the course of one day, it can wolf down up to three tons of krill.

“At the beginning of the feeding season, they’re going bonkers,” says Ari Friedlaender, an ecologist at the University of California Santa Cruz who has worked with WWF to unlock the mystery of whale feeding around the Antarctic Peninsula. Perhaps not surprising when there are more than 700 trillion adult krill in the Southern Ocean for the whales to gorge themselves on.

At this time of year, newly melted Antarctic ice creates a lens of freshwater near the surface where krill feed on plankton. Humpbacks feast on the krill every hour of the day— and this early in the season, there are 24 hours of daylight.

Among the keystone species in the Antarctic, krill depend on sea ice for both food and shelter. During winter, they live under the ice, grazing on microalgae called phytoplankton.

Humpbacks bubble net feeding in the Antarctic. © WWF-Australia / UCSC / Chris Johnson. Imagery collected under scientific permits: NMFS #23095, ACA #021-006.

“If you have a lot of sea ice, you'll have a lot of krill surviving their first winter,” explains Friedlaender. This cohort of krill provides food for many animals, including whales, seabirds, and seals.

Lunge feeders, like humpbacks, minkes, fin and sei whales, are found in both Arctic and Antarctic. While all feed on krill, humpbacks are the most abundant krill predator in the Antarctic, visiting the region from around December, when they arrive from the tropics. Different populations trek south each year from the same breeding grounds, whether that’s in the Colombian Pacific, Mozambique, Madagascar, the Great Barrier Reef, or elsewhere.

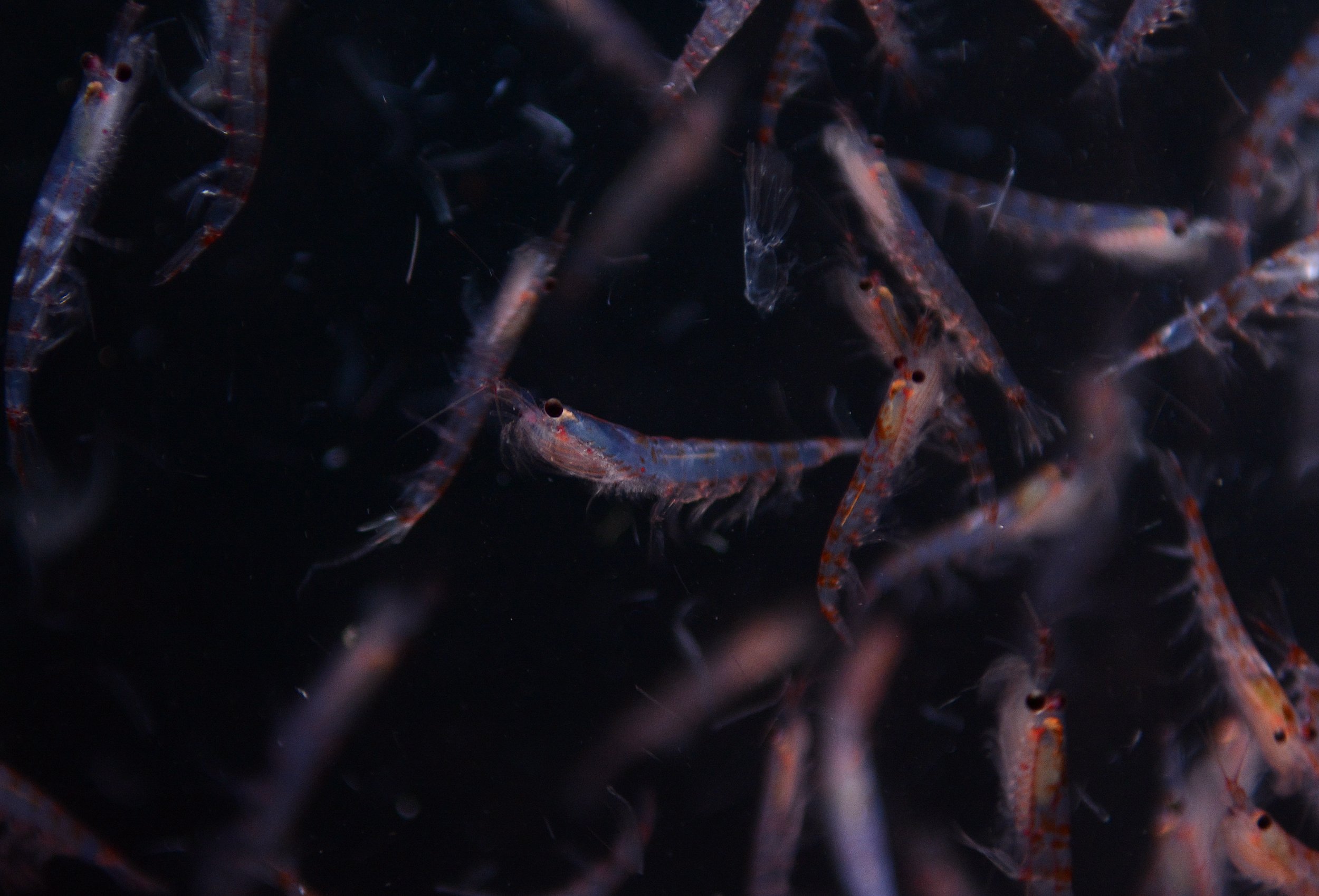

Antarctic krill (2024) © Ryan Reisinger

As the season progresses, and night time returns, the krill starts making daily migrations between the surface and deeper waters. The humpbacks start feeding less frequently, mostly eating at night when it’s most efficient to pick their prey off near the surface.

In the Arctic, on the other side of our blue planet, bulk filter-feeders like bowhead whales swim close to the surface with their mouths agape, scooping up plankton and krill, while gray whales slurp up crustaceans from the mud on the seafloor. Humpbacks that migrate here every year, feed not only on krill but also fish (while in the Antarctic, krill is the staple food on their menu).

The catastrophic impacts of melting sea ice

Unfortunately, as the climate changes, the Antarctic is warming and there is less sea ice, particularly further north where there is no land boundary and it melts into the ocean. Desperately searching for their vital habitat, the krill are shifting further south, which in turn forces whales to travel further—using more energy—to feed.

There are also more frequent bad years and fewer good years for sea ice, which is disastrous for krill and the animals that feed on them. “It's a very compact food web so any interruption can have quick, catastrophic impacts on the ecosystem,” says Logan Pallin, a whale biologist at UC Santa Cruz whose work explores how whales are responding to a changing environment.

Melting sea ice in the Antarctica (2010) © Wim van Passel / WWF

With less food, whales can’t put on as much weight so it’s harder to survive and reproduce. Female southern right whales, for example, are 23 per cent thinner than in the 1980s.

“The summer after a year with both low sea ice and low krill, there's fewer pregnant humpbacks,” reveals Pallin, because pregnancy and then nursing a calf takes so much energy.

Some scientists are warning that the effects of climate change on whale food availability in the polar regions will be so significant that some of the best recovery success stories for whales will be no more. One study predicts not only concerning declines in baleen whale populations, but even some local extinctions over the next 75 years.

DID YOU KNOW?

Antarctic sea ice reached record lows in 2023 and over 40 years krill have moved south by around 440 kilometres – that’s further than the distance between London and Paris.

An iceberg in the Antarctic Peninsula, 2018. © WWF-Aus / Chris Johnson

There are also more frequent bad years and fewer good years for sea ice, which is disastrous for krill and the animals that feed on them. “It's a very compact food web so any interruption can have quick, catastrophic impacts on the ecosystem,” says Logan Pallin, a whale biologist at UC Santa Cruz whose work explores how whales are responding to a changing environment.

With less food, whales can’t put on as much weight so it’s harder to survive and reproduce. Female southern right whales, for example, are 23 per cent thinner than in the 1980s.

“The summer after a year with both low sea ice and low krill, there's fewer pregnant humpbacks,” reveals Pallin, because pregnancy and then nursing a calf takes so much energy.

Some scientists are warning that the effects of climate change on whale food availability in the polar regions will be so significant that some of the best recovery success stories for whales will be no more. One study predicts not only concerning declines in baleen whale populations, but even some local extinctions over the next 75 years.

Competing for krill in the Southern Ocean

Krill fishing vessel among a supergroup of c.1,000 fin whales feeding on krill in South Orkney Islands (2022). © Conor Ryan

Another major threat to whales and their polar feeding grounds is unsustainable and poorly managed commercial krill fishing. “In the Antarctic it’s directly overlapping with critical feeding areas,” says Friedlaender.

The risk of this whale food source becoming limited is very real – partly because of the huge amounts of krill being caught for commercial use. Feeding is also more dangerous for whales in this area as the animals could get entangled in fishing gear or even struck by boats.

Luckily, the potential solution is straightforward, Friedlaender says: managing exactly where these fisheries operate and how much krill they take out of the environment.

There have been efforts to do just that. At the last meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) – an international body responsible for conserving Antarctic marine life – participants considered setting up new marine protected areas in the region and refining the fishery’s management plan.

DID YOU KNOW?

CCAMLR is an international body made up of 26 nations plus the European Union that was created in 1980 to oversee the conservation of marine life and ecosystems in the Southern Ocean.

A whale fluke in the Antarctic, 2023. © Paul Fahy / WWF Australia

Unfortunately, the opportunity to better protect krill, and as a result – whales, was lost. CCAMLR failed to reach a consensus on those important measures and, to make matters even worse, allowed a key existing measure, which reduces overlap between industrial krill fishing vessels and wildlife, to lapse. With all these ill-judged decisions, the Commission has taken a substantial step backward, realistically failing to meet its own objective of conservation.

Human threats impacting the amount, seasonality, and distribution of sea ice and krill could cause a mismatch between when whales visit Antarctica and when their food is available. “The whales are thousands of miles away,” says Friedlaender. “They don't know what the conditions are like where they're going until they get there.”

In the long-term, if whales are visiting the feeding grounds at times when there isn’t plentiful krill, it could impact not only the health of individuals but even whole populations. The ripple effect could be felt by marine ecosystems around the world, as so many other species rely on whales.

Ice-dependent Arctic species feel the pinch

In the Arctic, the same threat – climate change – manifests itself somewhat differently. Retreating sea ice opens habitats up for more industrial activity, bringing “a whole suite of threats: [underwater] noise pollution, ship strikes, potential fishing gear interactions as commercial fish stocks move north, and more,” Friedlaender says.

Narwhal showing tusks above water surface in the Baffin Island, Nunavut, Canada. © Eric Baccega / naturepl.com / WWF

Bowhead whales have evolved to thrive in icy Arctic waters. “As the ice retreats, less ice-tolerant species—like gray whales and humpbacks—can move in,” he says.

Although they’re not competing for exactly the same food—bowheads feed on krill and copepods, humpbacks on krill and fish, and gray whales on crustaceans—there are signs that whales' food sources in the Arctic are being hit by the effects of climate change.Unusual Mortality Events (UME) in gray whale populations have even been linked to these changes in the Arctic sea ice cover and prey availability.

Learning how to protect whales – and their blue corridors – better

“There isn’t a catch all solution,” says Pallin. “Each of the problems in these areas needs to be addressed individually,” and backed up by real-time scientific data.

With support from WWF, scientists like Friedlaender and Pallin are studying how climate change is threatening these whales and their habitats, and how to protect them even more effectively.

A researcher and conservationist retrieving a special dart with a biopsy sample © Paul Fahy / WWF-Australia

One research method includes collecting biopsies – skin and blubber samples – using a crossbow with a modified dart. “We collect a little bit of skin about half the size of your pinky finger,” says Pallin. From this tiny sample, researchers can figure out if an animal is pregnant and learn about its stress levels, diet, sexual maturity, and whether it has ingested plastic or other pollutants.

As critical hotspots for many whale species, both polar regions are in urgent need of protection. Recent reports by WWF and partners highlight “blue corridors”- crucial whale migratory routes that are becoming more perilous to navigate. Some species are found year round across these icy waters, while others migrate thousands of kilometers across ocean basins between polar and tropical seas. Protecting these pathways will allow them to move between their critical habitats safely, with reduced risk of ship strikes, entanglement, or pollution.

Benefits that whales bring

But this isn’t just about whales. Keeping these gentle giants healthy benefits everything in our seas. They are “the ocean’s trees,” says Pallin. When they consume prey, they fertilize marine ecosystems by dispersing nutrients through their faeces after feeding. This allows oxygen-producing phytoplankton to grow, supporting the entire food web.

Humpback whale breaching in front of a whale watching boat near Juneau, Alaska, US © Bruce D. Taubert

Healthy marine habitats are also vital for coastal communities that rely on the ocean for their food and livelihoods. For many, eco-tourism is a huge part of their economy. As of 2009, the whale watching industry contributed over $2 billion to the global economy while generating over 13,000 jobs. Annually, nearly 13 million people around the world go whale watching!

What we do, matters

The threats that whales face in the polar regions and elsewhere are directly linked to our everyday actions at home and beyond. From the food we eat, to the way we shop, commute or travel, all our lifestyle choices matter – and each of us can have a positive impact by making responsible decisions.

Humpback whale’s fluke in Alaska, USA © Sylvia Earle / WWF

Reducing our carbon emissions, making sustainable seafood choices, and advocating for policies that support marine conservation are just some examples of how you and I can help protect these gentle giants well into the future.

“We're at a critical juncture to try to understand and find ways to mitigate threats across breeding and feeding grounds, and those migratory corridors,” concludes Pallin.

RELATED RESOURCES

Challenges and solutions for migratory whales navigating national and international seas

A collaborative report from WWF and partners provides the first truly comprehensive look at whale migrations and the threats they face across all oceans, highlighting how the cumulative impacts from industrial fishing, ship strikes, pollution, habitat loss, and climate change are creating a hazardous and sometimes fatal obstacle course for the marine species.

Safeguarding migrating whales from growing pressures for a connected Arctic Ocean

An online report highlights the urgency of taking concrete action to safeguard Arctic whales on their migrations, as they are faced with new and growing pressure from climate change and increased shipping activity.