Uncovering the lives of whales to better understand our oceans

Studying humpback whales with drones and digital tags along the Antarctic Peninsula. Photo © Duke University Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab. Permit under NOAA.

WWF has been working with partners to conserve whales for over 50 years. They are awe-inspiring, yet difficult to study in the open ocean. Because of this, their distribution and critical ocean habitats — areas where they feed, mate, give birth, nurse young, socialize or migrate for their survival — are still being discovered. This is why we’ve invested in innovative techniques to better understand the lives of our ocean giants.

New technologies are allowing us to study whales and the ocean in new ways. Over recent years, WWF has supported field work such as using digital tags and drones to better understand how and where whales feed to uncover their favorite hotspots. It gives us a window into their world, to understand the health of populations, how they are affected by climate change, and how we might protect their critical ocean habitats worldwide.

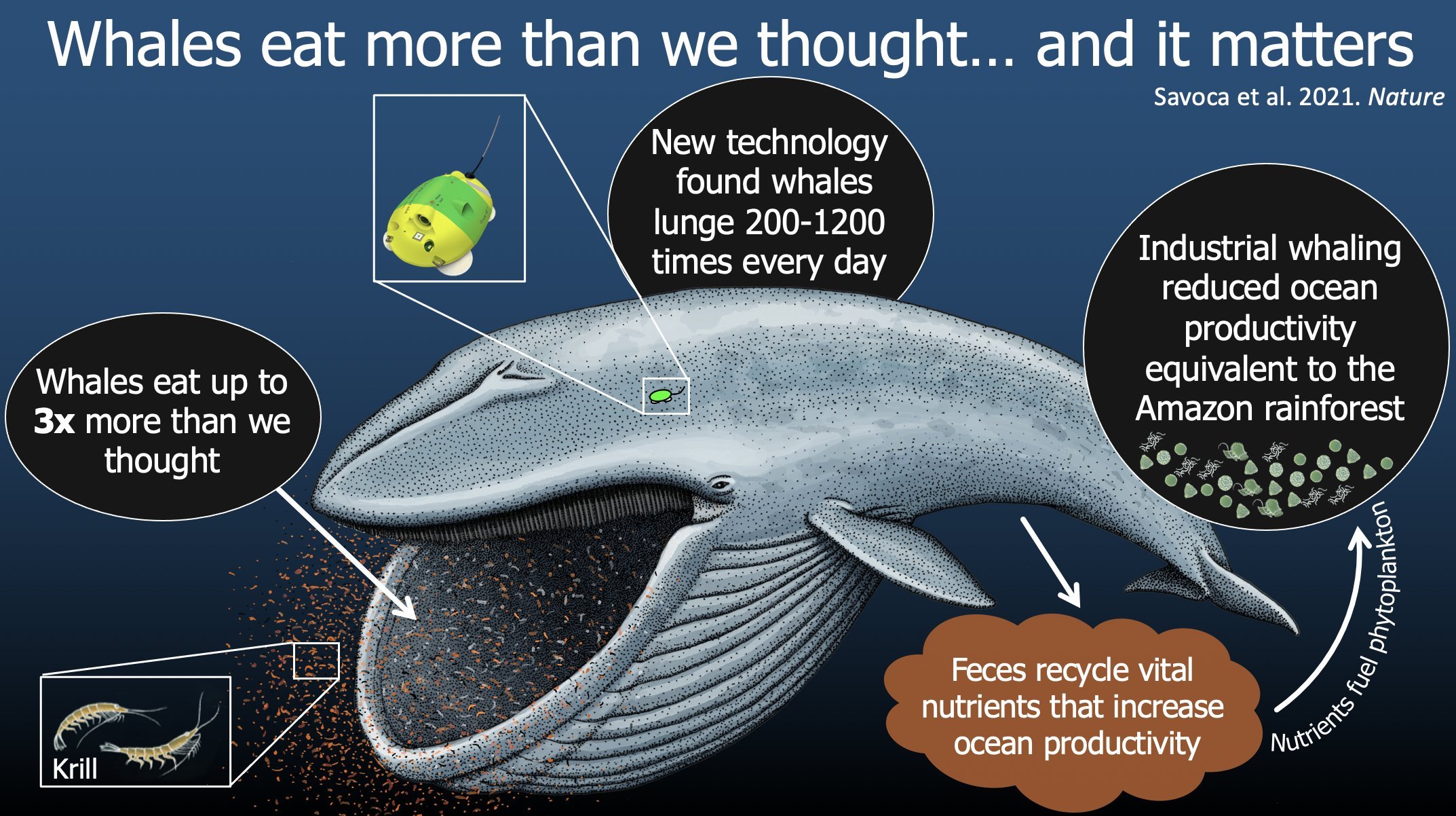

Marine conservation that makes a difference takes collaboration. Long-time science partners from University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) and Duke University Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab (MaRRS) with others from Stanford University published research in the journal Naturethat finds baleen whales eat at three times more than previously thought.

Dr. Ari Friedlaender, a whale ecologist from the UC Santa Cruz, and a long-time collaborator with WWF, explains why this is important: “By understanding how much prey whales consume we can also more accurately and effectively manage how we as humans use marine resources so that we can ensure there is enough food for whales. These animals are not just great consumers, they are vital parts of maintaining and enhancing ocean productivity.”

Using this new toolbox of technologies, including over 300 digital tags the size of an iPhones with suction cups, they analyzed an array of information on baleen whales such as blue, fin, humpback and minke whales. Baleen whales feed by gulping a large amount of water and filtering it through their mouths’ fringed baleen plates until only their prey remains. It turns out, an individual blue whale eats an average of 16 tons of food every day — about three times more than scientists had thought.

Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) with a ‘whale cam’ or a CATS suction cup video tag, Antarctic Peninsula. © WWF-Aus / Chris Johnson

One area of focus was on the Southern Ocean, where baleen whales feed on krill — a key species of the marine food web. Here, they devour up to 30 percent of their body weight in krill each day. Previous estimates suggested baleen whales consume less than 5 percent of their body weight daily.

Importantly, after all of this eating, comes pooping. Recently, scientists have realized that this helps fertilize our oceans and boosts the growth of phytoplankton, tiny life forms at the bottom of the marine food web that are eaten by krill. It’s another example of the important relationships and dependencies between predator and prey.

Researchers feel that if we restore whale populations to pre-whaling levels, we’ll restore a huge amount of lost function to ocean ecosystems. It’s helping nature help itself, and all of us who depend on it.

“WWF’s commitment to supporting this research has allowed us to be able to make fundamental leaps in our knowledge about whales, ocean ecosystems, and how we should be protecting them,” says Dr. Friedlaender.

Courtesty of Matt Savoca @DJShearwater (Savoca et al. 2021, NATURE)